What AI gets right — and wrong — about personal finance and investing

Can AI actually help manage your money?

I asked ChatGPT to build me a budget. It told me it needed specifics, or else it would be, in its words, “guessy.”

Whenever anyone on the internet asks for “specifics,” I get nervous. (Too close calls on Facebook Marketplace; if you know, you know.) That left me wondering: What data should I give it for an accurate budget, and what data would expose me to security risks? And, how instructive would it be? Could it tell me which stocks to put in my Roth IRA?

I’m not the only one asking these types of questions. Sixty-six percent of Americans, including over 80% of Gen Z and millennials, have used generative AI for financial advice. But of those who have acted on it, 52% said they made a bad decision because of the information they received.

The question: Is AI a reliable personal finance tool, and if so, what should we use it for?

Advisor.ai

The New York Times profiled a couple people who used AI to create budgeting plans and to find strategies for paying down debt. The advice they received was largely helpful and responsible — essentially a personalized amalgam of information you would find on Investopedia, banks, credit union websites, and excellent personal finance books.

You shouldn’t tell AI everything, though. This is a good list of specifics to avoid sharing.

Using AI for basic financial literacy is much different than using it as an investment guru. There is evidence that AI can improve stock picks but only after it’s received extensive data and specific instructions.

Researchers at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business trained a version of ChatGPT-4 using professional financial forecasting techniques and found that it predicted company earnings more accurately than human analysts — 60% accuracy versus 57%. The model’s predictions supported a strategy that earned returns well above what normal market risk would explain — about 12% per year on a risk-adjusted basis.

Another study from the National Bureau of Economic Research showed that a specially trained AI model predicted stock prices one year ahead more accurately than human analysts. A strategy that invested based on disagreements between AI and human analysts consistently beat the market by nearly 1% per month.

These studies do not prove that AI on its own is a good stock picker. They prove that very smart people can devise models that can beat the market using AI.

Assuming that you can use AI to beat the market because trained professionals do is like saying you can create Michelin-starred cuisine because you also have a kitchen.

AI can perform better than human analysts likely because it can digest and process massive quantities of information — and because it doesn’t suffer from the same biases that humans do.

Humans still beat AI predictors when making forecasts for smaller companies and those with asset-light business models (when there is less data for the AI to ingest).

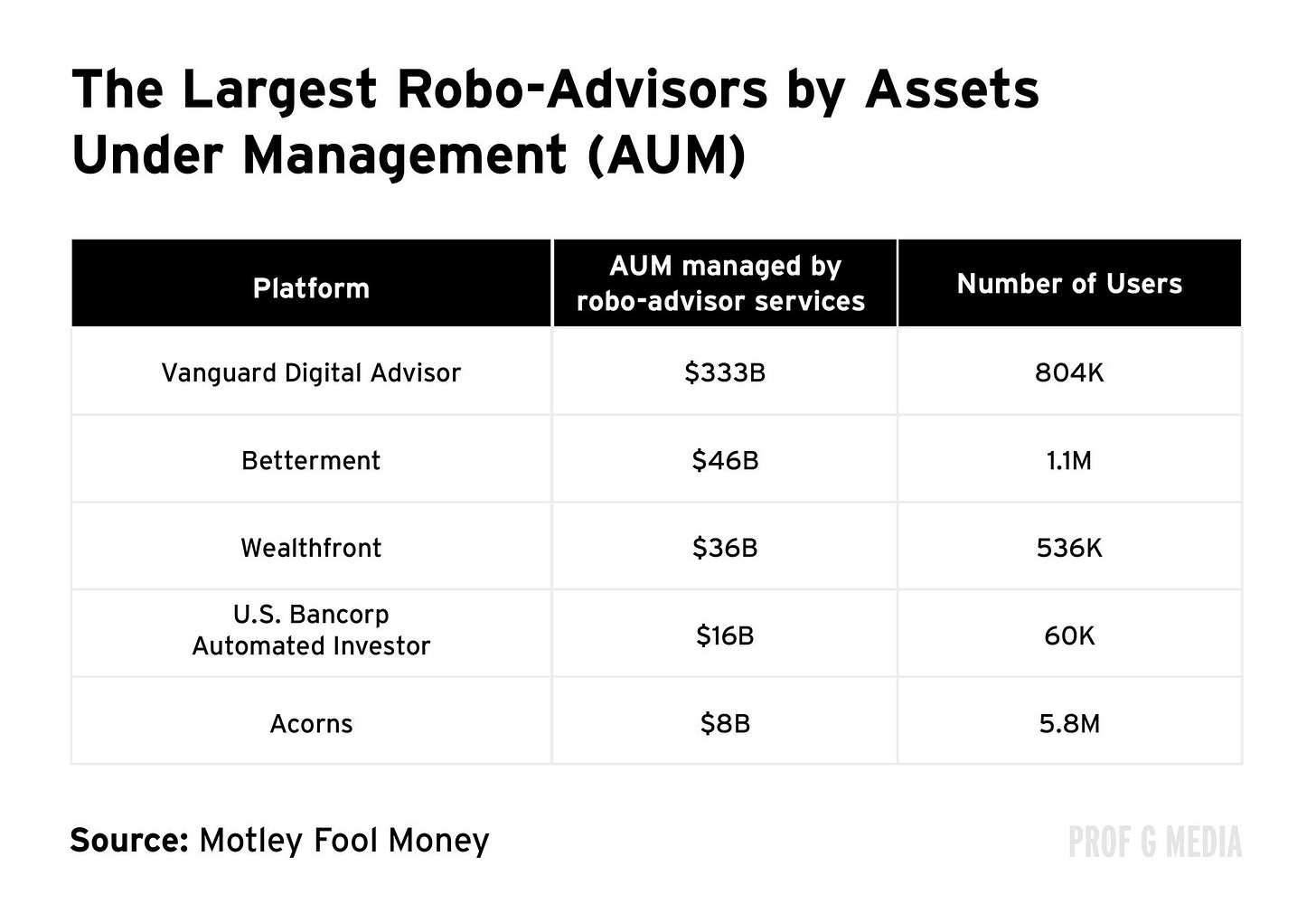

Most normal people who successfully employ AI in their financial life are using a product that has been around since 2008 — a robo-advisor. A robo-advisor is an algorithm-driven service that asks questions about your financial goals, then uses that information to automatically invest for you.

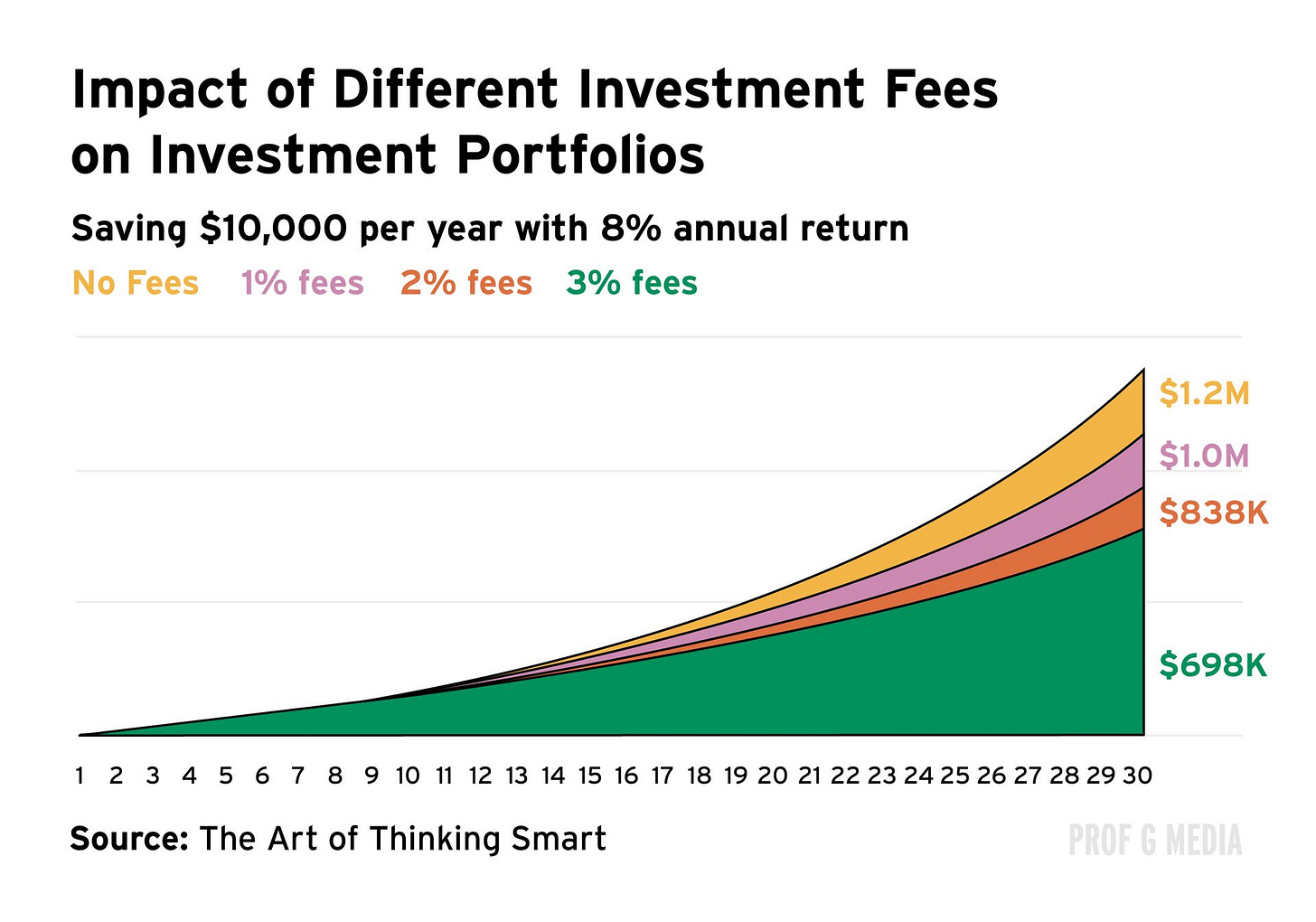

Robo advisors offer several concrete advantages. Research shows that investors who use robo-advisors suffer lighter losses during downturns, are more diversified, and pay less in fees.

The latter point is a significant one. Most robo-advisors charge annual flat fees of roughly 0.25%, much less than the typical 1% charged by a human financial planner. That might not sound like a lot, but it could easily add up to thousands of dollars in savings over time.

The robo-advisory business is expanding quickly: The market is expected to grow from $62 billion in revenues as of 2024 to $470 billion in 2029 — a 600% increase.

This is still tiny compared with the broader market. Investment advisors in the U.S. manage a collective $145 trillion in assets.

While robo-advisors are good for basic investing guidance, if you need estate-planning services or complicated tax management, you’re better off consulting a human.

The Original Sin

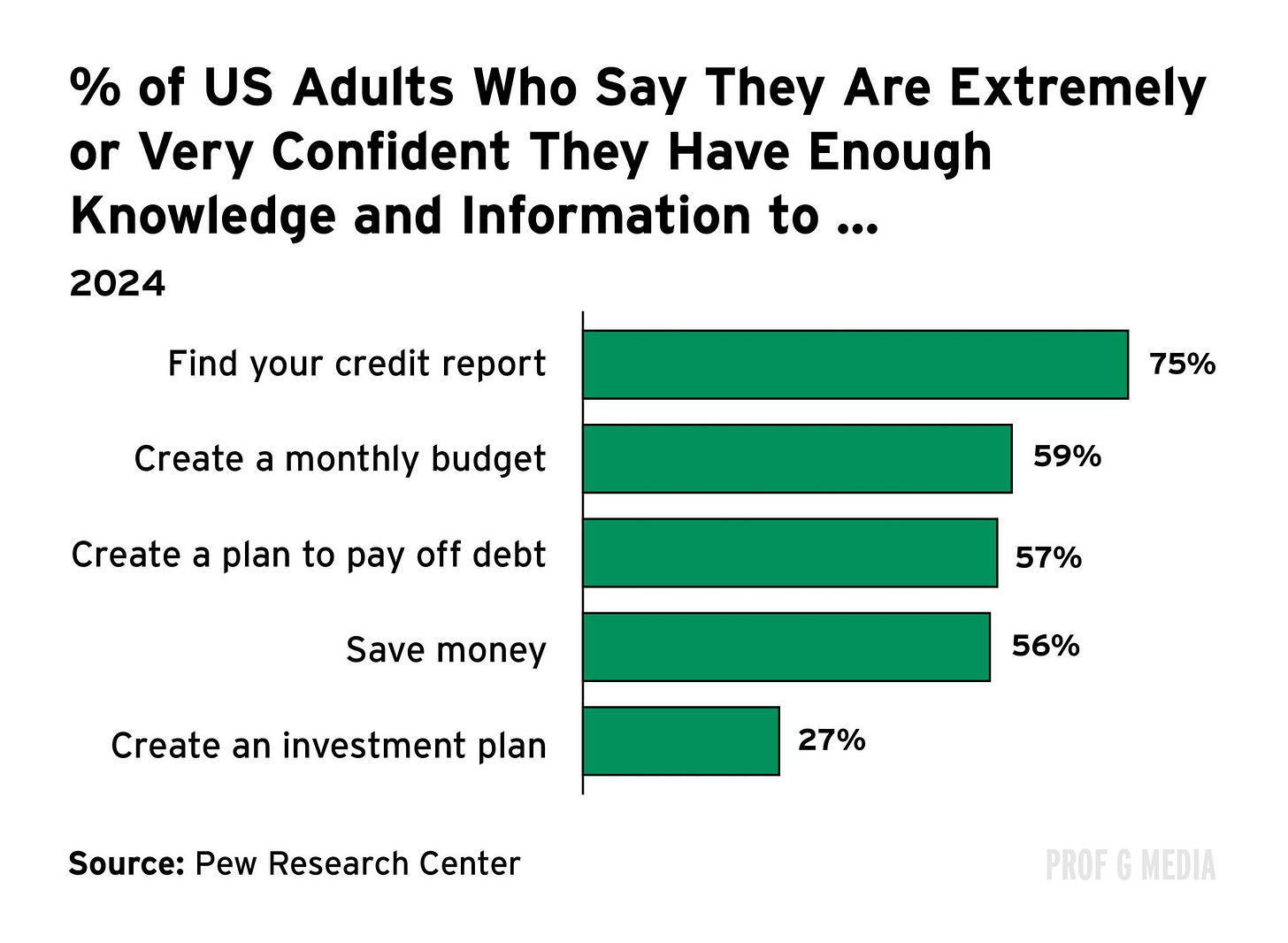

So many of us ask AI financial questions because American schools do a terrible job preparing young people for the financial realities of being an adult.

We were taught that the mitochondrion is the powerhouse of cells, but we never learned how to pay a credit card on time.

Worse, we’ve maligned talking about money to a point where people are scared to ask questions: Three-quarters of those who asked AI for advice did so because they would be too embarrassed to ask other people.

There is near universal agreement that financial concepts should be taught in high school; yet, only seven states — Alabama, Iowa, Mississippi, Missouri, Tennessee, Utah and Virginia — currently require students to take a semester-long personal finance course.

Professors at the Wharton School and the George Washington School of Business developed three questions that are commonly used to assess financial literacy. In 2021, less than 30% of Americans answered all three questions correctly. See if you can do better (answer key at the end).

1. Suppose you had $100 in a savings account and the interest rate was 2% per year. After five years, how much do you think you would have in the account if you left the money to grow?

A) More than $102

B) Exactly $102

C) Less than $102

D) Do not know

2. Imagine that the interest rate on your savings account was 1% per year and inflation was 2% per year. After one year, how much would you be able to buy with the money in this account?

A) More than today

B) Exactly the same

C) Less than today

D) Do not know

3. Please tell me whether this statement is true or false. “Buying a single company’s stock usually provides a safer return than a stock mutual fund.”

A) True

B) False

C) Do not know

*Answers below

Learning personal finance in high school overwhelmingly improves credit scores, reduces the use of risky services like payday lending, and increases debt repayment rates.

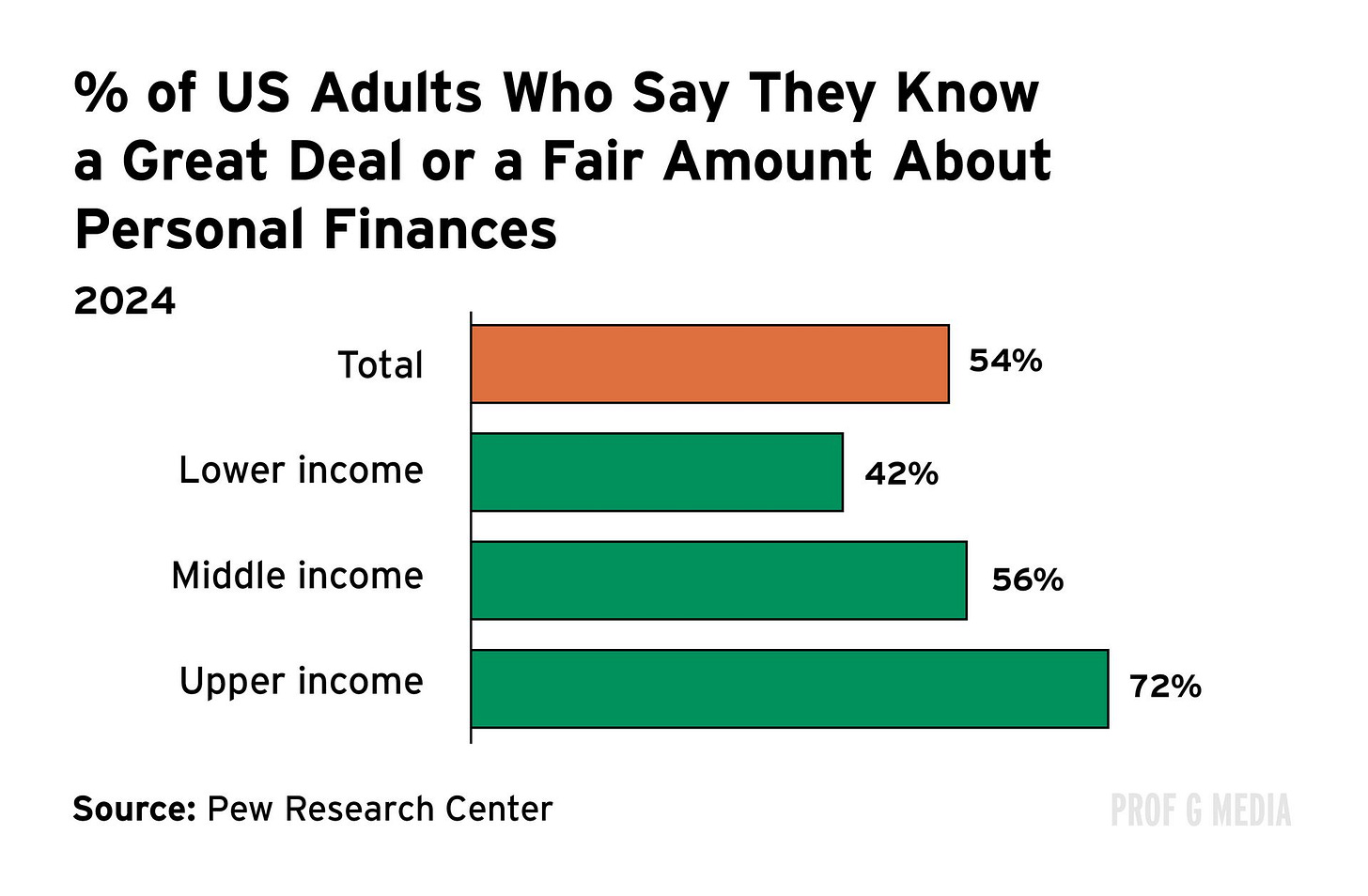

Like playing polo, taking frequent ski trips, or saying phrases such as “we’re comfortable,” understanding money and investing is directionally predictive of your household income. One in five Americans with household incomes less than $47,800 say they don’t know much or anything at all about personal finance compared with only 4% of those with incomes greater than $143,000.

This knowledge gap is insidious and partly to blame for growing income inequality. An estimated 30% to 40% of wealth inequality near retirement can be attributed to financial literacy.

This makes sense: Having no foundational understanding of how wealth accumulates makes it very hard to accumulate wealth.

Can AI help? Yes. AI can create low-risk, diversified investment portfolios, and offer advice on basic financial topics like how to make a budget or how to pay a credit card on time.

But AI is a tool – not a magic wand. Unless you are a skilled and lucky professional investor, trying to beat the market remains a statistically doomed undertaking.

*Answers: 1. A; 2. C; 3. B

TRUE